martian-computing

CS 498MC Martian Computing at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

A Prospectus for Our Enquiry

Learning Objectives

- Enumerate the components of Urbit (Urbit OS, Urbit ID, Arvo structure).

- Enumerate at least three use cases for Urbit.

- Diagram the high-level architecture of Urbit.

- Explain kelvin versioning.

There is probably more reading, and certainly more philosophy, in this lesson than in all the rest put together. Bear with me.

Why Urbit (or Something Like It) Matters

I make three indictments of the current state of affairs:

- Data are pwned.

- The system is pwned.

- Identity is pwned.

Data are pwned. In cryptocurrency circles, there is a saying: if you don’t own your keys, you don’t own your coins. It has become clear that we are the most precious commodity online. In particular, we don’t have the freedom or capability to move our data between services. If a project goes down, it may well catch all of your carefully curated tags, bookmarks, images, contacts, and research data with it. (I postpone the discussion of identity.)

Savvy corporations are careful to avoid vendor lock-in, a dependence on a vendor’s products cultivated again and again by major service providers. Even companies like Google that loudly proclaimed support for “data liberation” use this like a lanternfish to later replace open protocols (like Google Talk) with proprietary ones (Google Hangouts). Companies with lawyers and a deep and thoughtful vested interest have a hard time navigating this minefield—the average consumer has little chance of success.

The system is pwned. Computers today feel no faster than they did in 2005, and the reason is not to be laid like a wreath on the tomb of Moore’s Law. Software bloat is out of control, and grows more, not less, acute with every new OS version.

For the most part, there are no sufficient incentives for real developers to simplify software rather than make it more complex. Minimalist software design remains a hobby of hackers and code golfers.

Beyond this, open-source software is frequently broken in practice. There are a number of mordant observations that can be made:

-

FOSS has a parasitic model. Most real innovation happens outside of open-source projects, which are often clones of more successful proprietary software packages (LibreOffice/Microsoft Office, GIMP/Adobe Photoshop, Inkscape/Adobe Illustrator), and/or a clever way for a company to farm out development to free labor (OpenOffice/Oracle, Ubuntu/Canonical, Darwin/Apple). Thus even FOSS successes are often copies of proprietary antecedents.

-

FOSS suffers from what one observer has dubbed “financial deficiency disease.” Even popular, well-used packages may have little oversight and funding for developers. OpenSSL, for instance, was found in 2014 to have only one full-time developer despite being used by 66% of Internet users. Very few companies have succeeded in being FOSS-first (as opposed to FOSS-sometimes).

-

FOSS has a hard time responding to customer demands. The DIY ethos espoused by FOSS developers often leads to middle fingers when features are requested. It is difficult to imagine a software company responding to a well-meaning customer with, “If you need it, why don’t you build it yourself?” (Conversely, has anyone worked with a small startup hungry for a market? I have had that privilege, and they were responsive and professional. They considered my input and feature requests seriously, because I stood, to them, as representative of a class of users.)

We have a cascading stack of legacy software and strange interdependencies. We have an anemic FOSS program in general. Taken together, actually getting the functionality you want as a user often requires a proprietary platform anyway.

Even if one of these things could be fixed, the underlying OS philosophy is broken in many ways anyway. We’ve come a long way from the old noblesse oblige of Unix: do one small thing and do it well. Microsoft Windows never had that ethos, and macOS and Linux have long since abandoned it.

The open-source ecosystem we have today (built on GNU+Linux/OpenBSD/FreeBSD) is fundamentally broken, and even if it were not broken, it is abstractly imperfect: it can be fixed but never correct.

- Optional Reading: Maciej Cegłowski, “The Website Obesity Crisis”

- Optional Reading: Maciej Cegłowski, “Build a Better Monster: Morality, Machine Learning, and Mass Surveillance”

- Optional Reading: Mark Tarver, “The Cathedral and the Bizarre”

Identity is pwned. We as users do not own our data, we do not know what corporations know about us, and we have no control over how our data are used, sold, traded, or lost.

Data breaches grow larger ever year, and affect corporations of every size in every industry. Sometimes these breaches are the result of clever social engineering; more frequently, someone forgets to salt the password hashes or just stores or transmits them in unencrypted plaintext; sometimes, the data are just left available at a deprecated or forgotten API endpoint. The point is, identity security is really hard to get right in practice, and those who have custody of your data are frequently subject to moral hazard.

- 2013: Evernote, 50 million records

- 2014: Ebay, 145 million records

- 2015: Ashley Madison, 32 million records

- 2016: Yahoo!, 1 billion records

- 2017: Experian, 147 million records

- 2019: Facebook, 850 million records

- 2019: CapitalOne, 106 million records

(It is worth keeping in mind that “records” does not equal “people” or even “accounts,” though.) Data are from Juliana de Groot, “The History of Data Breaches” and Wikipedia, “List of Data Breaches”.

Identity itself is cheap: it costs botnets and spammers nothing to spin up new email addresses and new false identities. Game-theoretically, spammers thrive in an environment where identity is close to free.

Identity is also dear: losing a password in a breach can cause at best hours of resetting service logins and at worst the trauma and legal process of recovering from identity theft.

- Optional Reading: John Ohno (

enkiv2), “Big and small computing”

Altogether, these flaws in the current system render it unsuitable for building the future.

What Urbit Is

Let me offer three quotes to explain what Urbit is:

“Urbit is a clean slate reimagining of the operating system as an ‘overlay OS’, and a decentralized digital identity system including username, network address and crypto wallet.” (Tlon)

“It’s ultimately a hosted OS (it resides on top of Linux) with an immutable file system with the additional purpose that you build applications distributed-first in a manner where clients store their own data. There’s also other stuff in there obviously with Hoon and Nock and all that.” (

scarejunba)

“It’s perhaps how you’d do computing in a post-singularity world, where computational speed and bandwidth are infinite, and what’s valuable is security, trust, creativity, and collaboration. It’s essentially a combination of a programming language, OS, virtual machine, social network, and digital identity platform.” (Alex Krupp)

Your Urbit is a personal server built as a functional-as-in-language operating system that runs as a virtual machine on top of whatever. (Sometimes the developers refer to this as a “hosted OS,” but they don’t mean as in VMWare or VirtualBox or even containerization.)

The Urbit vision is the unification of services and data around a scarce futureproof identity on an innately secure platform. All of these objectives are laudatory.

For our academic purposes, Urbit provides an excellent example of a visionary complex system which is radical (returning to the roots of computing) and forward-looking—and yet still small enough for us to grok all of the major moving parts in the system. We will refer to documentary materials produced by the Tlon Corporation, the primary developers and custodians of Urbit, but Urbit itself is open-source.

As you can imagine, the documents produced by Tlon are frequently as partisan as the documents produced by the Linux Foundation. While we make frequent reference to those documents, we are operating as scholars, free per our ideals of undue influence. I myself am cautiously optimistic about Urbit’s potential to solve many problems faced by legacy computing and networking systems, but I seek to see clearly without rose-colored lenses. Urbit is worthy of study in its own right as a compelling clean-state architecture embracing several innovative ideas at its base, and our discussion should not be construed as advocacy but scholarship.

- Optional Reading: Tlon Corporation, “Urbit Primer” (the older introduction)

- Optional Reading: Jorge Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqgar, Orbis Tertius” (a fascinating short story and the inspiration for Tlon’s name; also what GPT-3 feels like)

What Urbit Is Not

As a “hosted OS,” Urbit doesn’t seek to replace mainline operating systems. Indeed, presumptively its Nock virtual machine could be run quite close to the bare metal, but Urbit itself would still require some provision of memory management, hardware drivers, and input/output services. Urbit’s goal instead is to replace the insecure messaging and service platforms and protocols used across the current web.

The Components of Urbit

Briefly put, Urbit requires you to have an Urbit OS (which runs your code, stores your data, etc.) and an Urbit ID (which demonstrates your ownership of said code and data).

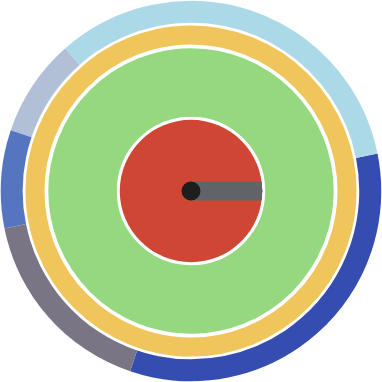

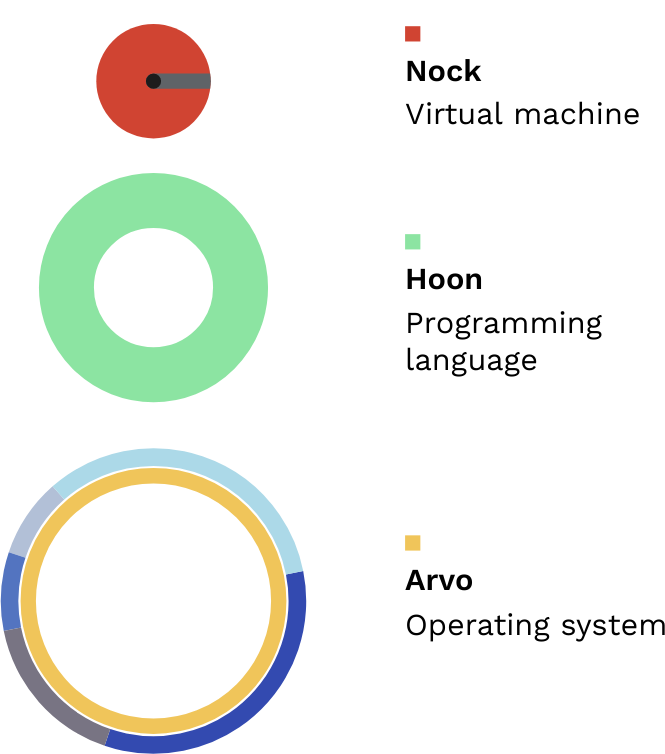

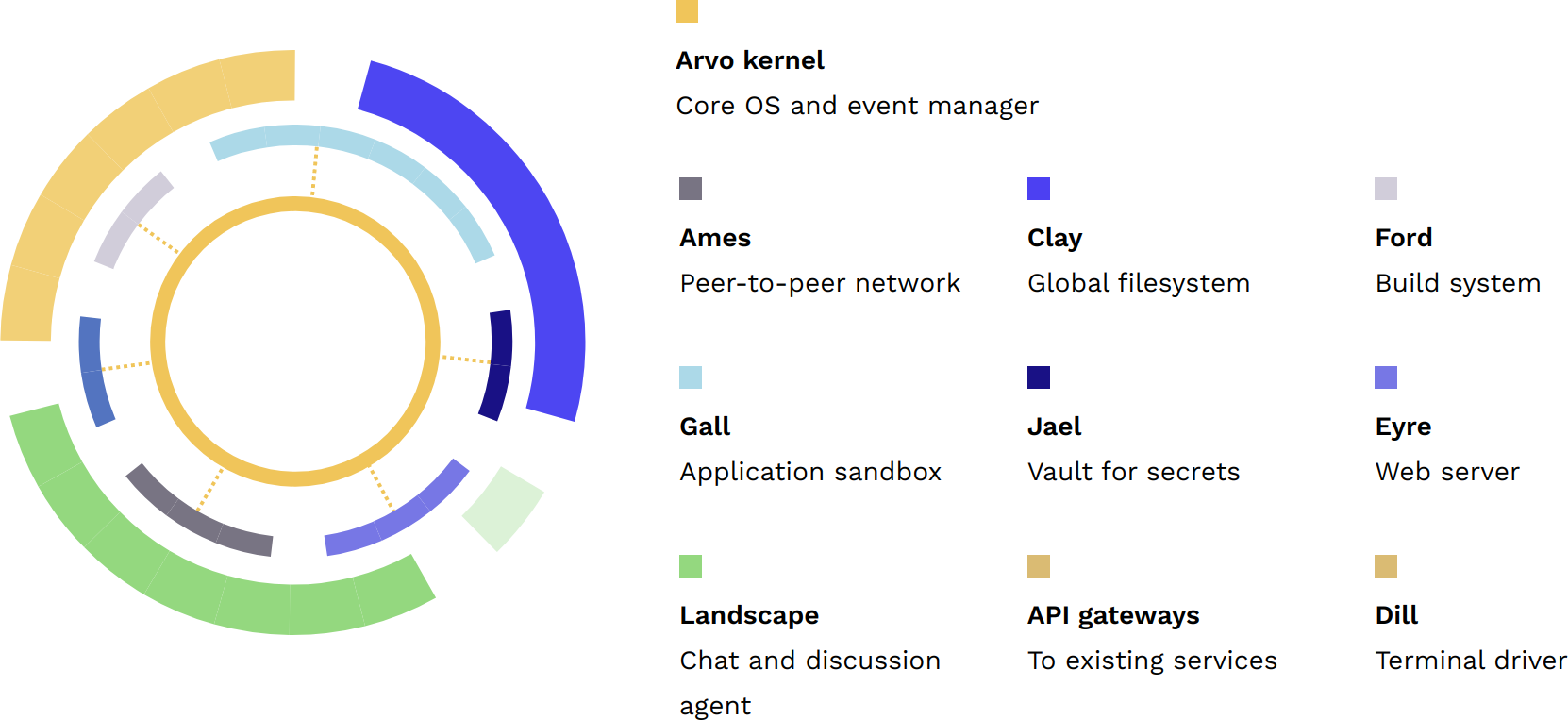

Urbit OS. The Urbit OS operates on top of the Nock virtual machine, and broadly consists of Arvo and its vanes. A schematic representation is frequently used:

At its base, Arvo is an encrypted event log (or equivalently an operating function). The Nock virtual machine is like Urbit’s version of assembler language, and it may in theory be implemented on top of any hardware. Hoon is Urbit’s equivalent of C, a higher-level language with useful macros and APIs for building out software. Arvo runs atop these definitions.

You can think of Urbit OS as a virtual machine which allows everything upstack to be agnostic to the hardware, and handles everything downstack. Urbit has sometimes been described as an operating function, and this is what that means. Everything is implemented as a stateful instance, called a “ship” (see Urbit ID below).

The vanes provide services: Ames provides network interactivity, Clay provides filesystem services, Ford provides builds, etc. On top of these, userspace apps

We will take a closer look at every part of this system as we move forward through the course.

Urbit ID. I noted above that Urbit OS is an encrypted event log. Urbit also acts as a universal single sign-on (SSO) for the platform and for services instrumented to work with Urbit calls. Since the Urbit address space is finite, each Urbit ID has inherent value within the system and should be a closely guarded secret. An instantiation of your Urbit ID is frequently called a ship, which lodges on your filesystem at a folder called a pier.

Urbit IDs have mnemonic names attached to them, although fundamentally they are only a number in the address space. For instance, my address on Urbit is ~lagrev-nocfep, the unique ID I own, corresponding to the 32-bit address 0xFC730500 in hexadecimal. We’ll talk more about the address space, the naming scheme, and Urbit ID in Azimuth 1.

How Does Urbit Stack Up?

I raised three indictments of the way things are today:

- Data are pwned.

- The system is pwned.

- Identity is pwned.

In the Urbit model, users provide data to service endpoints, retaining their data rather than farming it out. While no control can be exercised over data once sent out, a proposed reputation system can penalize bad actors in the system with reduced network access and other sanctions.

The system is designed to be transparent. Something that runs on the Nock VM is of necessity open-source—no binary blobs! (As with Ken Thompson’s “Reflections on Trusting Trust”, you can’t necessarily trust what’s below completely, but that’s a problem with any system you didn’t build yourself from the bare metal up.)

Identity is scarce and stable, much like moving into a house. The SSO aspect of the system means that you have to remember and use many fewer passwords, and the cryptographic security layers means that as long as you treat your master key like your Bitcoin wallet you will have perpetual security.

All in all, Urbit like Bitcoin and (the best) blockchain applications seeks to securely deliver on the aims of the old Cypherpunk movement of the 1980s and 1990s: digital security, digital autonomy.

- Optional Listening: Understanding Urbit Podcast [blog entry]

Huh?

At this point, you may feel confused as to what exactly Urbit is. That’s understandable: it’s hard to explain a new system in full until it has started to manifest new and interesting features with broader repercussions, and I’m hardly the apostle of legibility myself. For comparison, consider the following two interviews from much earlier in the history of the public Internet:

- Optional Watching: Bill Gates on David Letterman, 1995 (an attempt to explain the Internet before almost anyone grokked it)

- Optional Watching: David Bowie on BBC, 1999 (a prophecy which grasps the essence without the technicality)

On this basis, it’s safe to say that Gates got it, but Bowie “got it.” Their interviewers, by and large, did not.

A Frozen Operating System

The philosophy underlying Urbit bears a strange resemblance to mathematics: rather than running always as fast as one can to stay in the same place (a Red Queen’s race), one should instead establish a firm foundation on which to erect all future enterprises. In this view, the operating system should provide a permanently future-proof platform for launching your applications and storing your data—rather than a pastiche of hardware platforms and network specifications, all of that is hidden, “driver-like.” The OS should explicitly obscure all of that and no reaching beneath the OS should be allowed.

From the docs:

Normally, when normal people release normal software, they count by fractions, and they count up. Thus, they can keep extending and revising their systems incrementally. This is generally considered a good thing. It generally is.

In some cases, however, specifications needs to be permanently frozen. This requirement is generally found in the context of standards. Some standards are extensible or versionable, but some are not. ASCII, for instance, is perma-frozen. So is IPv4 (its relationship to IPv6 is little more than nominal - if they were really the same protocol, they’d have the same ethertype). Moreover, many standards render themselves incompatible in practice through excessive enthusiasm for extensibility. They may not be perma-frozen, but they probably should be.

The true, Martian way to perma-freeze a system is what I call Kelvin versioning. In Kelvin versioning, releases count down by integer degrees Kelvin. At absolute zero, the system can no longer be changed. At 1K, one more modification is possible. And so on.

In other words, Urbit is intended to cool towards absolute zero, at which point its specification is locked in forever and no further changes are countenanced. This doesn’t apply to everything in the system—”there simply isn’t that much that needs to be versioned with a kelvin” (~nidsut-tomdun)—but it does apply to the most core components in the system.

In this light, when we talk about Urbit we talk about three things:

- Crystal Urbit (the promised frozen core, 0K)

- Fluid Urbit (the practice, mercurial and turbulent but starting to take shape)

- Mechanical Urbit (the under-the-hood elements, still a chaos lurching into being, although much less primeval than before)

(I often think of the hypothetical structure of Jupiter: clouds over a sea of metallic hydrogen over a diamond as big as Earth.)

- Reading: Curtis Yarvin

~sorreg-namtyv& Galen Wolfe-Pauly-ravmel-ropdyl, “Towards a Frozen Operating System” - Reading: Paul Graham, “The Hundred-Year Language”

- Optional Reading: Jared Tobin

~nidsut-tomdun, “UP9: Kelvin Versioning for Arvo” (the first email in the thread) - Optional Reading: Peter Bhat Harkins, “Finished Libraries”

- Optional Listening: Castle Island Podcast, “Episode 17, Urbit”

Caveats

Urbit is not, of course, perfect, and if you peruse the Hacker News threads concerning it you will find many who think that it tilts at windmills. Not everyone agrees with the criticisms I leveled above, nor with the necessity for breaking compatibility. Beyond this, Urbit is far from a fait accompli—it could well go the way of Ted Nelson’s Project Xanadu, which inspired much of the modern web but remained mired in technical difficulties despite its breadth of vision. (Ted Nelson has worked on Xanadu since 1960.)

Many think that it is better to attempt to fix the challenges of data control, privacy, and equity on the current web: Sovrin, WebAssembly, IPFS, Holochain, Space, and Scuttlebutt each, in their own way, attack the same problems that Urbit seeks to dissolve. (And there are many more such projects, to be certain.) In that sense, Urbit is an arbitrary choice for our study, but one that I think holds much promise.

At this point, Urbit is also rather slow. Partly this is due to development effort being spent on Arvo and userspace rather than on the virtual machine layer (currently Vere but with King Haskell in development). One trick is to think of Urbit as ideal for a world in which computation and network bandwidth are too cheap to meter, a world we hope to inhabit someday.

At the end of the course, we will also circle back around and discuss the most cogent criticisms—at which point you will be well-qualified to engage in the dialectic.

- Optional Reading: Mark Tarver, “The Bipolar Lisp Programmer”

Comment

Our interest and our discussion are technical and independent of the founder of any particular project. And while speaking as a professor I don’t endorse Urbit as anything other than an object of study, I’d like to also make it clear that letting me teach this course does not imply University or department promotion or endorsement of Urbit, its founder, its stakeholders, or whatever political or philosophical motivations may underlie its impetus.

A more recent discussion of Urbit distances the platform from “digital feudalism”: “Urbit’s distribution and sponsorship hierarchy of galaxies, stars and planets is not designed as a political structure, or even a social structure. The actual social layer is in userspace – one layer up.” (This is probably a context-free statement right now, but we’ll examine what the distributed hierarchy is in Azimuth 1.)

Urbit is a decentralized network of social networks. No one can regulate it. Urbit is made to blossom into an endless garden of human cultures, each of which must regulate itself, none of which can bother the others. The soil in which these flowers grow must be level and neutral.

For what it’s worth, other than a lively spectrum of political opinion, I haven’t found the Urbit community to be overtly political in any direction. That doesn’t negate your experience or concerns on the matter, and if you find something that makes you uncomfortable, please let me know.

- Optional Reading: Francis Tseng, “Who Owns the Stars?” # in the final lesson

- Optional Reading: Curtis Yarvin

~sorreg-namtyv, “A Founder’s Farewell”